History of Pius X Mission

The Pius X Mission: Resident School for Native Children was a Catholic boarding school that operated in Skagway, Alaska, from 1932 to 1959. Like many residential schools of its era, it was established to assimilate Indigenous children into Western culture through education, religious instruction, and labor. Over its 27 years of operation, the mission left a profound and complex legacy, shaped by its dual role as both a place of refuge for some and a source of trauma for others.

Founding and the Early Years

Reasons for the Pius X Mission

.Image courtesy of the BC Archives, Sisters of St. Ann Archives collection, MS-3606)

The Origins and Father Gallant

Education in Alaska, for Alaska Native children, was disjointed from before the territory’s purchase in 1867 into the late 20th century. At the time Alaska was purchased, Alaska Natives were not considered American Indians but rather populations of Asian origin. Because of this, responsibilities regarding education remained fuzzy for decades. In 1905, Congress empowered Alaska to develop a formal school system; however, they did not include direction for the education of Native children. This led to a segregated school system where Euro-American children attended public schools, and Native children largely attended religious schools. These religious schools in Alaska often fell below the standards of the public education system. Even though this was addressed on the surface in 1917, when legislation was passed for federal funding for Alaska Native education, the segregated system remained embedded.

While legislation had required schools in communities with eight or more children, this was primarily applied to white communities, and Native children in remote areas were sent away to schools in other parts of Alaska or even the Lower 48.

Many of the Alaska Native children attending boarding schools, including the Pius X Mission, faced various types of hardships in their homes and communities. This has led to a long-standing viewpoint that missions, boarding schools, and religious institutions “saved” these children from bad home lives. However, it is important to remember that it was the communal effort between settlers, missionaries, and industry that led to devastating disruption for Alaska Native families and communities through disease and displacement. Diseases like smallpox, tuberculosis, and measles devastated entire villages, often killing elders and knowledge-holders and leaving families fragmented. At the same time, traditional economies were upended by the fur trade, mining booms, and forced relocation, displacing people from their ancestral lands and lifeways. Essentially, the hardships were created by incoming forces, and then those same hardships were used to justify the boarding school system that was designed to assimilate Alaska Native children into Euro-American culture.

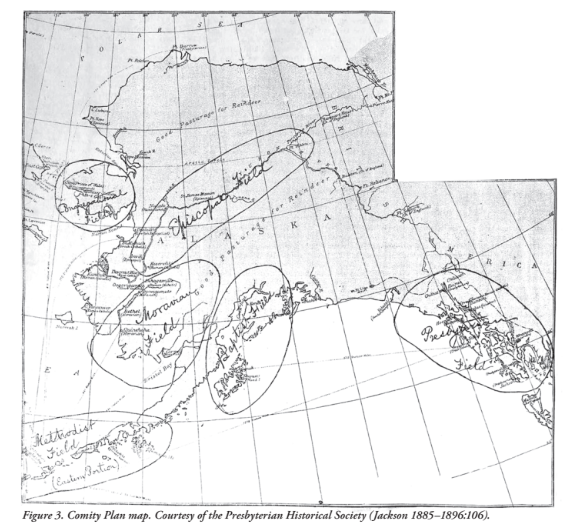

Sheldon Jackson, who played a vital role in the establishment of mission schools in Alaska, credited mining success in Alaska to the mission schools making the Alaska Native populations “docile.” This was a strategy that had been utilized earlier in Wind River, where Jackson was credited with “domesticating” the Sioux population so land could be opened to extraction. In 1880, Sheldon Jackson, along with representatives from the Presbyterian, Methodist, American Baptist, and Episcopal churches (the Moravian, Congregationalist, and Roman Catholic churches were included later), met to agree on the distribution of their missionary efforts in Alaska. During the meeting, a map was laid out and areas established where each denomination would focus their efforts. Analysis of the meeting, maps, and records demonstrates that the distribution of missionary efforts in Alaska was coordinated with the intent of facilitating resource extraction, including gold, lumber, fish, coal, pelts, and transport opportunities.

For more information about Sheldon Jackson’s role in Alaska Native boarding schools and interdenominational coordination related to missionary work and resource extraction, we recommend reading “The Alaskan ‘Comity Plan’ and Its Continued Effects on Indigenous Peoples” by Benjamin Jacuk, published in The Alaska Journal of Anthropology, Vol. 22, 2024.

The first thoughts of Catholic expansion into Skagway began in 1885 with an enthusiastic archbishop in Victoria. However, it wasn’t until more than a decade later, during the height of the Gold Rush, that Father Turnell requested to be assigned there to minister to both the residents and the transient, gold rush population. He remodeled an empty store into St. Mark’s Church and remained in Skagway until 1918, when Father Gallant replaced him.

Image courtesy of the BC Archives, Sisters of St. Ann Archives collection, MS-3606)

The Sisters of St Ann

Our records show that Father Gallant, founder and principal of the Pius X Mission, was a strong proponent of the once-proposed aluminum plant in Dyea. Gallant anticipated that it would return Skagway to a population similar to that of the Gold Rush. He even traveled to Washington, D.C., to lobby for the plant.

Image courtesy of the BC Archives, Sisters of St. Ann Archives collection, MS-3606)

According to the Sisters of St. Ann, the Pius X Mission was founded in response to a long-held desire of the missionary priests to have a Catholic school for Native children in Southeast Alaska that would “take them away from the harmful influence of sectarian or government institutions.”

From the accounts of the Sisters of St. Ann, it is clear that their primary focus was on the religious and cultural conversion of the students. Baptisms, first communions, and confirmations were meticulously recorded, and noted with pride. The Sisters’ hope was for the children to pass their new religion on to their families and communities.

Gallant received his first donation toward the Pius X Mission from J.M. Klein of Chicago, the son of the founder of Klein Tools, in memory of his late wife. The second donation came from a close friend at Princeton University. But it had been John O’Dea’s contribution that truly got the mission off the ground and it was John O’Dea who chose the name Pius X Mission. After these early contributions Father Gallant began purchasing land throughout Skagway. Over the course of his time there, he acquired more than 57 town lots and approximately 60 acres across the bridge north of town.

The cornerstone of the Pius X Mission was placed in August of 1931, and construction of what was called Crimont Hall, named after Alaska Bishop Crimont, was completed by December of the same year. At the time, this was considered only the first unit of the Mission. Father Gallant had plans for a much larger and grander institution in Skagway. Even as it stood, it was the most modern Native school in the territory of Alaska, boasting an oil-burner heating system, hot and cold running water, shower/baths, classrooms, dormitories, and a chapel. The construction of Crimont Hall cost $65,000.

Image courtesy of the BC Archives, Sisters of St. Ann Archives collection, MS-3606)

The Sisters of St. Ann, who served at the Pius X Mission in Skagway, also operated or staffed several residential schools in Canada where serious abuses have been documented. These include Kamloops Indian Residential School, Kuper Island Industrial School, and St. Eugene Mission School, sites where unmarked graves and widespread trauma have come to light in recent years. While each school’s history is unique, it is important to acknowledge this broader legacy when considering the role of religious institutions, including the Sisters of St. Ann, in the history of Native boarding schools across North America. Their presence in Skagway cannot be separated from this larger context.

In 2023, the Sisters of St. Ann willingly granted the Skagway Traditional Council access to their archival records related to the Pius X Mission.

Father George Edgar Gallant would become the founder and principal of the Pius X Mission. He was born in 1894 on Prince Edward Island. While studying at seminary in Oregon as a young man, he spent several summers working as a bookkeeper at the cannery near Haines, where he made the decision to spend his life in Alaska. World War I and concerns about Gallant being drafted into the Canadian army led to him being ordained earlier than usual, making him the first Catholic priest ordained in Alaska in early 1918. St. Mark’s in Skagway was Gallant’s first assignment.

Gallant began planning for a boarding school in Skagway shortly after taking over St. Mark’s. He began purchasing land for the school as early as 1924 after some early donations, but it was Bishop Crimont taking him to Rome in 1930 that helped make the school a reality. One evening in Rome, Gallant came upon a group of American tourists in the lounge where he was staying. They were looking for a fourth player in a game of bridge. Gallant joined, and over cards, he spoke of his ambitions to establish a mission for Native children in Skagway. That same night, he secured a $30,000 donation from John F. O’Dea of Ohio. This was an early example of what would become a robust fundraising career for Gallant - one that would often keep him away from the mission in Skagway for extended periods. Accounts claim that Gallant continued to use bridge as a way to connect with wealthy and influential people.

In 1931, as the Pius X Mission in Skagway neared completion, a key question arose: Which religious order would be entrusted with the care and education of the Native children? Several communities were considered, including the Sisters of St. Ann. After much deliberation, a formal appeal was made by Bishop Crimont to the order’s Provincial House in Victoria. Just days later, the General Council approved the proposal, and the Sisters of St. Ann accepted the call to serve in Skagway’s new Catholic mission school.

In September 1932, Sisters began to arrive at the Mission from Victoria and Juneau. Bishop Crimont joined them, along with the Provincial Superior, to hold Mass and bless the school and its grounds. In addressing the Sisters, Bishop Crimont spoke of patience, compassion, and gentle discipline in working with the children, reminding them that “Indigenous children, in particular, were sensitive and carried long memories.” With his final blessing, the Sisters of St. Ann formally began their service at the Pius X Mission.

Image courtesy of the BC Archives, Sisters of St. Ann Archives collection, MS-3606)

Jacuk, Benjamin. “The Alaskan ‘Comity Plan’ and Its Continued Effects on Indigenous Peoples.” The Alaska Journal of Anthropology, vol. 22, 2024.

“Father told the children he was pleased and happy to see the Mission School a reality, and that their docile response to the efforts that were being made for their advancement in religion, school, and housing were the cause of real joy to him.”

***

“These children will return to their own villages in time and they will be apostles among their own people. At solemn high mass this morning 23 children received their First Holy Communion. It is a happy day for all. At present all the children at the mission are Catholics.”

***

“When the enrollment is increased to one hundred twenty, there will be that many more grateful hearts to “teach and instruct unto justice:””

Image courtesy of the BC Archives, Sisters of St. Ann Archives collection, MS-3606)

Image courtesy of Skagway Museum, Berg Collection - 2)

Image courtesy of the BC Archives, Sisters of St. Ann Archives collection, MS-3606)

The Students

On October 5, 1932, the first eight students arrived by boat from Juneau. A week and a half later, 23 more students arrived from Wrangell and Petersburg. Classes began in late February with 42 students who were, according to the Sisters, “almost all untrained in religion, work, manners, or order.” As their first order of business, the students sang their first benediction within a week of classes beginning.

In the early years of the Mission, most of the students who came to the mission spoke their native languages and were taught to speak English and Latin. In later years, many students came to the school already speaking English.

Over the 27 years the mission operated, students were brought there from communities all across Alaska. To date, there is no known single repository where student records for the Pius X Mission were kept. Skagway Traditional Council staff have been able to track down records for some years from both public and private collections; however, these records are incomplete, with almost no documentation from the 1930s and early 1940s. From the records uncovered so far, nearly 500 different student names have been identified, the youngest being only 3 years old. Accounts from the Sisters of St. Ann suggest there was an average of 71 students enrolled each school year with only 19 students in 1933-34 and 104 students in 1955-56. Student enrollment counts usually included how many baptisms were performed during that school year. In the 1950s, the school began taking on day students from the community.

Of the nearly 500 names recovered, the home communities of only a small percentage are known. Still, even this limited data shows that students came from as far away as Nome and Atka.

Records and recollections show that students were often brought to the mission a few at a time by various people — sometimes by visiting priests, sometimes accompanied by Sisters, and in other cases, they appear to have been simply put on a boat from Juneau.

The Sisters of St. Ann documented student arrivals in their internal chronicles, capturing both the practical realities and their own perceptions of the children. These records reflect the religious and colonial worldview of the time, including a strong belief in the superiority of Western culture and Catholicism, which influenced how they understood their mission and the children in their care.

“Eight students, the first to be admitted, arrive from Juneau in Mr. Steven’s gas boat.”

***

“The children arrive from their widely scattered homes and all are quite happy to be back at the Mission. Many are new pupils, some protestants and some Russian Catholics. Although the different protestants maintain several schools in Southeastern Alaska their children are coming to us year by year in ever-increasing numbers eager to be Catholics. Even the poor ignorant natives recognize the true church when given an opportunity.”

***

“Three new pupils arrive unexpectedly this evening from Juneau brought on Mr. Steven’s gas boat”

***

“Holidays were definitely ended today by the arrival of our charges. A larger number than ever before are in attendance and many more have registered and are expected to arrive soon”

Letter between Bishop Crimont and the Mother Provincial, 1933, discussing school capacity and attendance.

“ Father Gallant has not communicated with me since he left Skagway and I am in the dark as to his whereabouts and the results of his begging tour. Fr. Monroe has been entrusted with the car of rounding up the pupils with the cooperation of Fr. LeVasseur and Fr. Buckley. Fr. Buckley is sending three girls from Metlakatla. The others have to come from Wrangell, Petersberg, Juneau, Douglas, and Hoonah”

Letter courtesy of the BC Archives, Sisters of St. Ann Archives collection, MS-3606)

Letter contents made public by Sisters of St. Ann in North to Share, 1992.

“ I took one look at the long sidewalk (from the street to the school) and scared as we were it was like an endless doggone walk and one of those old nuns in those awful black heavy garments came out and gee what a cold chill I had. It took a long time to get used to that mission but eventually we got away from that lonesome feeling and made some good friends”

A former student’s account of first arriving at the Mission.

Quote taken from Skagway: City of a New Century by Jeff Brady

Life at the Mission

It is coming up on 100 years since the Pius X Mission opened in 1932, and 66 years have passed since it closed its doors. This passage of time limits our access to firsthand accounts of what it was like for students at the school. Some former students have shared their stories, offering valuable insight into life at the Mission. However, we currently have very limited firsthand accounts from students who attended during the first half of the school’s operation. This is a significant gap in our understanding, especially since available records suggest that the school’s dynamics shifted around World War II and after the Mission building was rebuilt following a fire in 1945.

The Sisters of St. Ann kept an internal record known as the Chronicles, documenting events, comings and goings, illnesses, and staffing. These records offer meaningful glimpses into daily life at the Mission, but it is important to remember that this account was made from a very different perspective from that of the students; the Sisters were adults, teachers, Catholics, missionaries, and Euro-Americans.

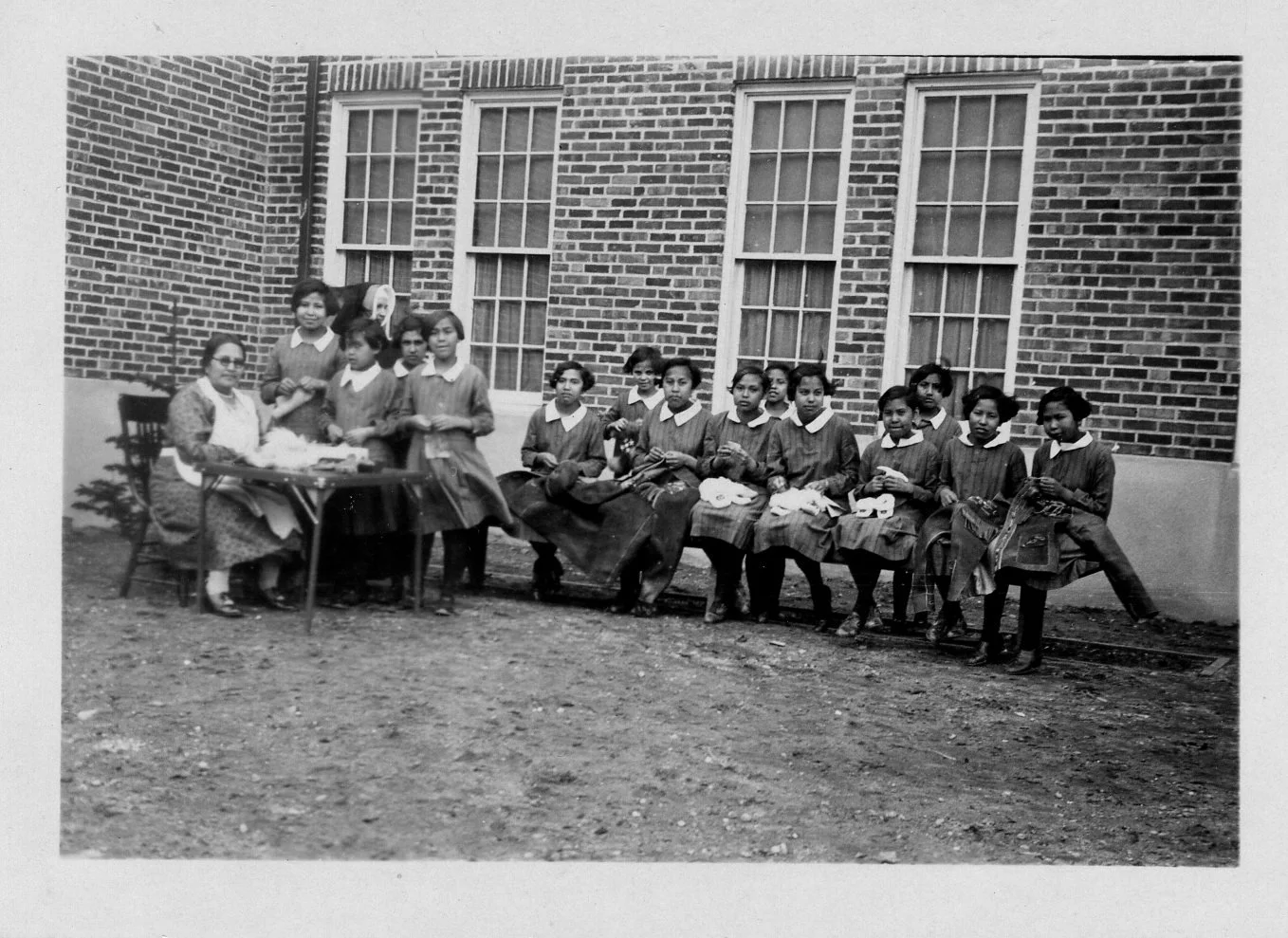

The student experience at the Mission appears to have varied over time and between the genders. In earlier years, accounts and photographs suggest a more rigid environment. Students wore matching uniforms, had their hair cut short in a uniform style, and marched. By the 1950s, however, there seems to have been some easing of these strict routines. Additionally, the experiences of boys and girls differed significantly. In the 1950s, older boys were reportedly allowed more freedom, while girls were only permitted to leave the Mission when accompanied by a Sister.

Image courtesy of the Skagway Museum, Dedman collection, MS-773

Accommodations and Food

Image courtesy of the Skagway Museum, Dedman collection, MS-2159

While Crimont Hall at the Pius X Mission was praised for its modern amenities, it still had its share of significant shortcomings. In the early years of the Mission, it was common for the pipes to freeze for a week or more at a time, or at times for the building to become so cold that students were kept in bed during the day just to stay warm. When the pipes froze, boys were tasked with hauling water from the river. The school also flooded during heavy rains. After the building was rebuilt in 1948, a nearby creek was diverted, but this may have worsened the problem. Former students recall regularly cleaning up floodwater from the ground floor.

Following the fire in 1945, student housing was moved to detached “cottages” - repurposed army barracks left over from the war. When first installed in the late 1940s, the Sisters described these cottages as comfortable and attractive. However, student accounts from the 1950s tell a different story: they remember the buildings as cold and damp, with rotting floorboards. When new Sisters arrived at the Mission in 1959, they immediately moved the children back into the main school building, citing the unsuitable and unsafe conditions in the cottages.

Food at the Mission seems to have been a case of feast or famine. The Sisters’ chronicles describe holiday celebrations with chicken or turkey, pies, and gifts of fruit, nuts, and candy, donated by the Skagway community, the army, or other sources. In some entries, it is clear that students shared in these celebrations; in others, it’s unclear whether the feasts included the children or only for the staff. Regardless, one of the most common and unhappy memories shared by former students is the food. Many recall eating oatmeal every day and hating it. Some remembered being served old military rations, including rotten peanuts and dry powdered eggs, while at the same time collecting fresh eggs from the Mission’s chickens, which were sold rather than eaten by the children. A former student said girls served dinner to the Sisters, priests, and staff and noted that their food was consistently better than students.

One former student recalled how the girls were responsible for serving food, while boys helped cook. If a girl liked a particular boy, she would crunch up the cornflakes at the bottom of his bowl before filling it the rest of the way, giving him a little more food than others. On the surface, it simply is a sweet gesture, but it also suggests the reality that students may have been hungry, even after meals.

Image courtesy of the BC Archives, Sisters of St. Ann Archives collection, MS-3606)

Aerial View of the Pius X Mission property c. 1948

“Those peanut shells were moldy and even though we had fresh eggs at the mission they never once served them to us - only egg powder.”

***

“She returned to Pius X and observed the barracks where the food as old as 10 years was still stored.”

***

“Thanksgiving Day is celebrated in the usual Catholic and American way: High Mass of Thanksgiving and general Communion and generous servings of roast turkey“

***

“Double feast - Bishop Crimont’s namesday and the anniversary of the election of our Mother General […] The children are given an apple and a banana treat.”

Education

The quality of education at the Pius X Mission is somewhat unclear. Some former students have given positive reviews of their schooling, even stating that the education they received at Pius was better than what was offered in public schools. The Mission also seemed to cultivate a reputation for academic excellence. However, official records and evaluations by the Commissioner of Education paint a more complicated picture.

In multiple years, the Commissioner of Education’s reports grouped Pius X Mission among schools deemed “unable to measure up to the standards of public schools,” citing issues such as understaffing, inadequately trained teachers, poor facilities, and a lack of basic supplies. Pius X was specifically noted as being unaccredited, and correspondence from the mid-1950s indicates that there were still “setbacks in instructional programs” stemming from the fire that destroyed the original building in 1945. A sanitation and engineering inspection conducted in 1961, after the school had closed, also found that classroom lighting did not meet minimum standards set by the American Standard Practice for School Lighting.

It is unclear whether this discrepancy between student experiences and official reports was due to shifting conditions over time, efforts by the Mission to conceal its shortcomings, or possible prejudice on the part of those evaluating the school.

Image courtesy of the BC Archives, Sisters of St. Ann Archives collection, MS-3606)

Image courtesy of the BC Archives, Sisters of St. Ann Archives collection, MS-3606)

Education at Pius X Mission covered a typical curriculum of reading, spelling, grammar, arithmetic, geography, history, science, physical education, and art, but over the years, also included vocational and practical training such as typing, shorthand, ceramics, dressmaking, and leatherwork. The mission was originally grade school up to 8th grade, but in 1948, the high school grades were added. In the early 1950s, there were plans to establish a laboratory to teach physics and chemistry, but there is no record that this ever came to fruition.

In 1939, Samuel Jackson of Skagway, a notable totem pole carver, began a class in wood carving for the boys at the mission. This is the only documentation found of the school fostering Alaska Native culture.

Father Gallant often emphasized the importance of education to the students at Pius, and many were encouraged to continue their schooling after leaving the Mission. Some went on to pursue further education in fields such as teaching, dental hygiene, and nursing. Over the years, many students joined the military, and some chose to stay and make Skagway their home.

A speech given to the graduating boys of 1953 emphasized the ideals:

“Be a saint, be a man, be a loyal American.”

an example of Mission school education’s instilling Christian, patriarchal, and nationalistic values.

Religious and Cultural Education

At the heart of the Pius X Mission’s curriculum was a deliberate effort to replace students’ traditional beliefs and lifeways with Catholic teachings and Euro-American cultural norms. Religious instruction was central to daily life at the Mission. Students were expected to attend Mass multiple times a day, recite prayers, and participate in sacraments such as baptism, first communion, and confirmation - events carefully recorded by the Sisters of St. Ann and celebrated with pride. One journal entry reads, “Our prayer is that these children will be Apostles among their own people,” underscoring the broader goal of training students not only to adopt Catholicism, but to spread it to their families and communities.

The Sisters viewed student devotion as evidence of success. One account records, “Our Lady must smile on these little Duskies as they clasp each bead in their little fingers and answer devotionally to the Hail Mary.” While likely seen as innocent and affectionate at the time, the language and sentiment reflect the racial and religious superiority that underpinned the Mission’s work, an assumption that Indigenous children needed to be spiritually rescued and reshaped.

Image courtesy of the BC Archives, Sisters of St. Ann Archives collection, MS-3606)

Image courtesy of the BC Archives, Sisters of St. Ann Archives collection, MS-3606)

In addition to religious instruction, Western holidays played a significant role in reinforcing Western cultural norms. At the Mission, students were introduced to and actively participated in holidays like Valentine’s Day, Halloween, Thanksgiving, Christmas, and the Fourth of July. Costume parties were held for Halloween, Valentine’s Day was celebrated with decorations and (in later years) dances, and Christmas always featured a large decorated tree with gifts for the children. These celebrations created joyful memories for many students and fostered emotional connections to Western traditions. Over time, these events helped to integrate the children into Euro-American cultural life and made them excited about Western holidays, further distancing them from their own traditional celebrations.

The Mission also embraced elements of popular American culture. In its later years, students held a spring recital that included a performance of The Music Man, a Maypole dance, and a final tableau depicting the Statue of Liberty, during which students sang a flag song and The Star-Spangled Banner. A prom-like event was even introduced, complete with the crowning of a king and queen. These activities not only brought a sense of fun and normalcy to life at the school but also worked to instill patriotic and cultural loyalty, forming students into what the system hoped would be disciplined, Christian, and “loyal American” citizens.

Beyond mainstream American holidays, the Pius X Mission also celebrated Catholic feast days, one of the most prominent being the Feast of the North American Martyrs. This annual event honored missionaries who were killed while attempting to convert Indigenous peoples in what is now Canada and the northern United States. For the Alaska Native children living at the school, this celebration likely sent a painful and confusing message. It upheld the idea that Indigenous identity needed to be changed or erased in order to be accepted by God, and that unconverted Native people were “the bad guy” and a threat to faithful Catholic missionaries. Rather than affirming the value of their heritage, the Mission placed honor on those who had tried to replace it. For many students, this could have contributed to feelings of shame, loss, and a sense of not belonging, both at the school and within their own culture.

A note made for the opening day of a school year :

“The Feast of the Jesuit Maryrs of America. Pius X Mission once more opens its portal to the descendants of the same Aborigines for whom the Martyrs’ blood besprinkled American Soil.”

In 1939 a visiting nun noted :

“These native children at their present stage of development may be classified as half and half. They speak English with an Indian accent; they dress like moderns and adopt the amenities of their white associations. On the other hand, they cling to their communal life in camps or huts, even to such as are built on stakes on the beach and they prefer the floor to chairs and tables. The manners which they put on while in school are easily discarded out of it”

Recreation, Music, and Sports

While life at the Pius X Mission was structured and oriented toward discipline, religious devotion and academic instruction, students did participate in a range of recreational and extracurricular activities. These activities often reinforced the school’s goals of assimilation, but they also created spaces for joy, creativity, and connection.

Father Gallant placed great emphasis on music as a tool for both discipline and character formation. In 1938, he purchased a full set of instruments for Pius X Mission and within a year, the Mission had established a well-regarded student band. Their first public recital was held on Easter Sunday in 1939. The school also had a choir and a Glee Club for a time, and students performed in community events such as Skagway’s Spring Recital, Silver Tea Party, and other local fundraisers for the Mission.

When the Sanatorium was in operation in Skagway, the students went there at Christmas to sing carols for the patients.

Image courtesy of the BC Archives, Sisters of St. Ann Archives collection, MS-3606)

One former student reflected,

“I guess my music is what I gained most from there. I still play the trumpet. They were excellent teachers. I grew up among regimentation with them, but you learned.”

Image courtesy of Marquette University, BCIM Collection

Music and the arts were a clear part of Gallant’s vision for an “accomplished” student. Children at the Mission also participated in theater productions, and poster design competitions. Mission students regularly won top prizes in poster contests, including events sponsored by the American Legion and the National Dental Week campaign.

Recreation also included sports, especially basketball. Pius X had a competitive team, and the Sisters kept records of the school’s wins and losses, although not very consistently. Girls and boys attended games in town. In 1930, after the local Boy Scouts refused to accept Native children, Father Gallant started a scout troop for the Pius X students, though with Gallant’s regular and extended absences for fund raising, it’s unclear how long it lasted.

Outside of formal activities, older boys sometimes went hunting and fishing or gathered food for the Mission along the Chilkoot Trail. The children on occasion went on picnics organized by the sisters - one time going all the way to Log Cabin on the train.

Another memorable presence at the Mission was its dogs. Over the years of operation, three Saint Bernards were residents of the school. The first, named Big Ben, and the last, Blizzard, served as companions to staff and students.

Image courtesy of Skagway Museum, Kasbohm Collection-1

Image courtesy of the BC Archives, Sisters of St. Ann Archives collection, MS-3606)

Student Labor

In addition to their academic and religious education, students at the Pius X Mission were expected to perform daily labor to help sustain the school. Like many boarding schools of its era, Pius X presented this labor as a form of education, vocational training, or character building. However, it also played a crucial role in the Mission’s ability to operate and raise funds

The school’s farm, known as the Mission Dairy, opened in 1937. Not long after, Father Gallant secured milk contracts with the Alaska Steamship Company and C.P.R. (possibly referring to the Canadian Pacific Railway), turning the dairy into a commercial enterprise. Older boys were responsible for tending to the farm, which included cows, chickens, pheasants and a pedigree Ayrshire bull. Father Gallant had an interest in birds and would go on trips to gather wild geese eggs often adding rare or undomesticated breeds to the flock.

In flood seasons, some boys even stayed overnight at the barns to monitor the animals. The work was demanding and, at times, hazardous. A former student recalled the grueling chore of cleaning out the chicken barns - an especially concerning task given the large number of birds (200 to 500 chicks hatched in some years) and the potential health risks involved. Exposure to dust and ammonia in enclosed chicken barns posed a serious danger to lung health, particularly in an era when tuberculosis was a constant threat.

Despite raising chickens and collecting hundreds of eggs, the children themselves were rarely allowed to eat them. The eggs, like the milk, were sold to help fund the Mission.

Image courtesy of the Skagway Museum, Dedman collection

Image courtesy of Marquette University, BCIM Collection

Beyond the dairy, children produced goods to be sold at the mission, particularly to appeal to tourists. Photos from the time show girls making leather goods, including fringe jackets and moccasins, styles that had little connection to Lingít culture, but matched non-Native expectations of what "Native" art should look like.

One account describes the jewelry-making program this way: “Children were taught jewelry making. It was hoped that in seeing gems come from unpolished, rough stones, they would learn that they, too, were gems.” While the sentiment may have been well-intentioned, it also reflects the belief that Indigenous children needed to be “refined” or “improved” by the institution

While students may have taken pride in the skills they learned or enjoyed certain aspects of the work, it’s important to recognize that much of the labor was mandatory, unpaid, and performed in service of the institution itself.

Health, Abuse, and Loss at the Mission

Like many boarding schools of its era, the Pius X Mission struggled with recurring illness, limited medical care, and conditions that would be considered hazardous by today’s standards. Students faced high rates of disease, physical hardship, and, in some cases, abuse. While some records suggest that children received annual medical and dental checkups, others reveal a pattern of chronic neglect and trauma, both physical and emotional.

In 1950, a visiting dentist treated 79 students. That single visit resulted in 55 tooth extractions and 317 fillings, a number that points to serious lapses in preventive dental care. Children were also examined for eyesight and tuberculosis and often had their tonsils removed on-site at the Mission. Commonly recorded illnesses included influenza, pneumonia, tonsillitis, measles, and tuberculosis. In one year, 45 students contracted the flu. When outbreaks occurred, school was often suspended and healthy students were enlisted to help care for the sick.

Tuberculosis was a constant threat. The Sisters occasionally implemented isolation protocols, and students were sometimes evacuated for treatment. Multiple students were flown to Juneau with TB, often dying days later, and in one case four months later. In total, at least six student deaths are confirmed in the records, with causes ranging from accidental injuries to tubercular meningitis and hemorrhaging. There is no indication that any children were buried on school grounds, but the records are incomplete.

Health at the Mission also intersected with physical control. Hygiene and appearance were emphasized. In the early years of the mission, uniform haircuts were enforced, and photos show girls with shaved heads, likely due to lice, but some schools shaved new students heads as a standard, regardless of finding lice and other schools shaved heads as punishment. Forced hair cutting has long been recognized as a form of cultural erasure and emotional abuse. Uniforms, controlled hairstyles, and rigid personal grooming standards were used to suppress individuality and enforce conformity.

Most disturbing are the records and oral accounts related to sexual abuse. The Sisters’ journals mention frequent visits from Catholic priests. At least 125 different priests stayed at the Mission over the years of operation. Some came to teach, others simply stayed for extended visits. Four of these priest have been accused or charged with sexual abuse. One served time in federal prison before returning to active ministry. Most notably, Father Cowgill, who served at the Pius X Mission from 1952 to 1959, is now officially confirmed to have been a pedophile.

Anonymous sources have shared additional accounts, including that a teacher with alcohol issues showed pornographic magazines to children, and that older students, upon discovering the abuse of younger peers, removed them from the school and hid them in a hotel for protection. In its final year of operation, the Mission struggled with increasing behavioral issues among students, possibly a symptom of unaddressed harm they were enduring.

Skagway and the “Mission Kids”

The relationship between Skagway, the Pius X Mission, and the students who attended the school is not easily unpacked. From the school’s origins, the city of Skagway supported the Pius X Mission. The city worked with Father Gallant to secure the land he needed, celebrated the establishment of the school, and facilitated its exemption from taxes. On the day the cornerstone was laid, the majority of the town attended, and the event was described as an “outstanding day in Skagway’s civic life.” The mayor praised the founders for their contributions, framing the school as an important step in the city’s progress.

Over the years, accounts from the Sisters of St. Ann describe the community supporting the school through financial donations and gifts for the children. When the school burned down in 1945, the community helped provide shelter for the students and assisted in replacing necessities and comforts in the weeks that followed.

Photographs and records show that students were also allowed to participate in public events. They appeared in Fourth of July parades, attended movies, and played basketball against the local public school.

However, the relationship between the Skagway community and the students was not without its challenges. The prejudice experienced by students can generally be divided into two types, though they overlapped and reinforced one another.

Image courtesy of the Skagway Museum, Dedman collection

First was Prejudice-based discrimination. Students were frequently treated as inferior, segregated, and viewed with suspicion, often being singled out or blamed first when something went wrong. Byron Mallot recalled that when incidents occurred in the community, “we thought we were the first folks to be called to task for some of those events.”

Segregation extended to public spaces and activities. Mission students attended the movie theatre only on chaperoned outings once a week or every other week. However, the children were regularly blamed for problems they did not cause. At one point, the mission stopped allowing students to attend, proving they were not responsible for the disruptions. In an interview, Stan Selmer noted how it was convenient to blame the “mission kids” for these problems, continuing that the term “mission kids” was often a polite cover for “Natives” who tended to be blamed for things just because of who they were.

The Alaska Native children in town were also excluded from the Boy Scouts, and the Pius basketball team’s opportunity to play was limited, as they were only able to compete against the Skagway public school because other schools in the area refused to play them.

Discrimination against the students has been described as “covert,” recognizing that it was difficult to determine whether they were targeted because they were Catholic, because they were Native, or both. One former student reflected, “There was some discrimination here, and a lot of it was towards the mission.”

Some students remembered the mission and Father Gallant as a place of reprieve from outside discrimination: “It didn’t matter what nationality you were, we all became Catholics,” a former student recalled.

The second form of discrimination faced by students was a combination of stereotyping, cultural caricaturing, and cultural exploitation. This involved oversimplifying Indigenous identity and using it for entertainment or profit. A photo of the 1955 Fourth of July parade in Skagway shows two young mission students dressed in Americanized “Indian” costumes that more closely resembled Plains cultures than Alaskan Native traditions. Students were used to create items to sell in support of the school. Photographs and records indicate that at least some of these items reflected Indigenous styles, suggesting that their cultural identity was being used as a selling point.

This photo, by Paul Sincic, shows Pius X Mission students preparing for a Fourth of July parade. At first glance, it appears that the mission may have been supporting Lingít culture, which is unusual for what is generally understood about the boarding school system and the mission’s objectives. It raised questions about the Pius X Mission having been somewhat of an exception among boarding schools by encouraging traditional culture. However, further research into records shows the parade float was designed as “Alaska Natives and their first priest.” Revealing that rather than honoring Indigenous culture, the float seems to have been celebrating Alaska Native conversion to Catholicism. This reflects the mission’s goal of assimilation rather than cultural preservation.

Staff: Gallant, the Sisters, Priests, and Teachers

Coming Soon

The Fire of 1945

In the early morning hours of November 16, 1945, fire broke out at the Pius X Mission. It started around 12:45 a.m., It was officially recorded as an electrical fire, but a former student says the kids knew it was from cigarette ash in the girls’ laundry bin. At the time, boys were permitted to smoke, but girls were not. (Brady)

The fire quickly engulfed the building. The entire top story was destroyed, and the ground floor was heavily damaged by water. The school’s chapel burned completely; sacred vestments, the ordination chalice, and other religious vessels were melted in the blaze. The sleeping quarters were upstairs, and with little time to respond, students and Sisters lost all their personal belongings and clothing.

One of the Sisters immediately called the fire department, and Father Gallant, who had not yet retired to his nearby home, was present to help. The evacuation only took minutes, with older boys carrying younger children out to safety. It had been a bitterly cold and windy night, and the children had to stand out on the street in just nightclothes, wrapped in blankets.

Image courtesy of the BC Archives, Sisters of St. Ann Archives collection, MS-3606)

Three weeks after the fire, Father Gallant left for Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles to begin raising funds for a new building. In the meantime, the school established a temporary home called “Pius X Mission Junior” in unused Army barracks on Broadway. Despite the circumstances, the Christmas spirit was kept alive that year. A large tree was put up in the dining hall on Christmas Eve, and the women of Skagway brought “boxes and boxes of cookies” for the children.

By February 1946, Gallant already had plans drawn up for the new building, but it would be another two years before the Mission was ready to move back in. In March 1948, the students and Sisters returned to a newly built school that featured expanded classroom space and a library. New sleeping quarters were placed in detached cottages connected to the school by a boardwalk. Though the Mission had survived the fire, the financial stress and disruption brought increasing tensions.

Image courtesy of the BC Archives, Sisters of St. Ann Archives collection, MS-3606)

The Skagway community stepped in to help. Children were first taken to the community hall and the Presbyterian church. Before the night was over, trucks brought them to the Skagway Sanatorium, where two hospital wards were made available. The Sisters there helped clothe the Mission staff, and more clothing arrived the next day, donated from Juneau. One Sister later recalled retrieving a few surviving belongings from the frozen remains of the building - including a set of dentures frozen in a block of ice.

The destruction was devastating, but there was an outpouring of support in the weeks that followed. The Sisters later described this as the “month of gifts,” with aid arriving from Skagway, Juneau, the Sanatorium, and other Sisters from British Columbia, Washington, and across Alaska.

Image courtesy of the BC Archives, Sisters of St. Ann Archives collection, MS-3606)

Final Years of the Mission and Its Closure

Strained Leadership and Repeated Requests to Leave

By the early 1950s, deep tensions were developing behind the scenes at the Pius X Mission. These issues, rooted in leadership disputes, financial strain, and shifting roles—ultimately led to the school's closure by the end of the decade.

The Sisters of St. Ann first arrived at the Pius X Mission in 1932 under an agreement with the Diocese of Juneau to provide education and domestic work in exchange for wages. Father Gallant held dominant authority at the Mission. When his plans or ideas conflicted with those of the Sisters, his decisions always prevailed. New Sisters arriving in the late 1940s described him as “the number one man,” and believed the school would have functioned better if the Sisters had been in charge. However, the Sisters still spoke of Gallant’s generosity, kindness, and devotion.

In 1950, Gallant met with the Territorial Board of Education and asked them to assume control of the school and employ the Sisters as staff. The Board declined. This meeting, while not mentioned in the Sisters’ records, appears in documents from the Commissioner of Education.

Just one year later, the Sisters began formally requesting to end their contract and withdraw from Skagway. Letters were sent again in 1952 and 1955, but the bishops in Juneau either denied the request or failed to respond. The reasons provided by the Sisters included the need to reassign personnel to places where young women might answer the call to become a Sister of St Ann, difficulty staffing an American mission with Canadian Sisters, and hopes that another congregation might take over.

Despite these explanations, it is notable that the Sisters expressed willingness to remain once Gallant departed, suggesting the root issues may have been more about leadership than logistics.

Image courtesy of Skagway Museum Archive, Dedman Collection

Unpaid Wages and Lack of Support

After the 1945 fire, the Sisters were no longer paid in any consistent or meaningful way. The original agreement had promised them $30 per month, but no regular payment was received after the fire. In some accounts, the Sisters’ eventual administrative takeover of the Mission in 1959 was framed as compensation for these unpaid wages. However, the written agreement only granted them temporary administrative duties for one year.

When the Sisters wrote to Gallant asking for help in finding a replacement order so they could withdraw, he refused. He told them it was “not his affair” and that any decisions in that direction would have to be made without him. “I am perfectly satisfied that all is in accord with God’s Holy Will,” he wrote.

His frequent fundraising trips were another major source of frustration. Not only did they weaken morale, but they also left the school without spiritual leadership. The Sisters’ 1932 contract had guaranteed that their spiritual needs would be met. Without a priest, there could be no Mass, and the Sisters noted this absence repeatedly in their Chronicles.

Image courtesy of the BC Archives, Sisters of St. Ann Archives collection, MS-3606)

Financial Confusion and Declining Morale

Though Gallant frequently described the school’s financial situation as dire, he was known to drive new cars and travel extensively. He failed to pay the Sisters’ wages and often fell behind on bills.

When Gallant was “unexpectedly” named pastor of Holy Family Church in Anchorage in 1959, he took with him the checks and tuition payments for the upcoming school year. The Mission’s safe, files, and school records were withheld from the Sisters. Father Cowgill, who had served at the Mission from 1952–1959, joined him in Anchorage.

The new priest assigned to Skagway after Gallant’s departure expressed serious concerns. He noted that both academically and morally, the school had a poor reputation, and believed it would take years to rebuild trust. He also questioned the cost and feasibility of continuing to operate such an isolated school with so few Catholic students.

Behavioral Challenges and Institutional Decline

By the late 1950s, the student population at Pius X began to shift. The Territory increasingly used the school to place children with behavioral issues, mental health needs, or social challenges. The Sisters became overwhelmed.

In one instance, a Sister was responsible for 27 boys, ages 5 to 14, without reasonable relief. One described the exhaustion of never having a break from caring for children. In 1959, several older boys, some as old as 20, were placed at the Mission by the welfare department. A report documented mental health issues in students at a level that surpassed what the Sisters were equipped to manage.

Just before his departure, Gallant accepted three more older boys into the school against the Sisters’ wishes, undermining their efforts to phase out that age group. When the school’s disciplinarian, became seriously ill and had to leave for treatment, it was the final breaking point. With no spiritual leadership, no administrative support, and more responsibility than they could manage, the Sisters made the difficult decision to close the school in December 1959.

Aftermath and Reconciliation

The closing of Pius X marked the end of turbulent times. One consequence was that the Sisters of St. Ann, who had been preparing to staff an interparish school in Anchorage, were rejected by Father Harley Baker, pastor of Holy Family in Anchorage, where Gallant had been reassigned after the Pius Mission. According to the Sisters, this reflected Gallant’s displeasure with their decision to close the school.

In 1968, however, some of the Sisters attended Gallant’s Golden Jubilee, honoring his fifty years as a priest. Their presence was seen as a gesture of reconciliation and a willingness to let go of the hurt they had endured during their final years at the Mission.

If you notice any details in the above history of the Pius X Mission that seem incorrect, need more context, or could be better represented, please reach out to us through our contact page.

Resources and Acknowledgements

This history was written using numerous sources, both public and private. We would like to acknowledge the published works of Jeff Brady, including his newspaper articles and his book Skagway: City of the New Century; Thomas Thornton, for his Ethnographic Overview and Assessment of the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park; Robert Dahl, for his book After the Gold Rush; and the Sisters of St. Ann for North to Share.