Research Updates

Finding Records

Skagway Traditional Council has undertaken a years-long effort to recover records from the Pius X Mission School, with the goal of better understanding the impacts it had on students, their families, and their communities. This work has not been easy. Records for Pius X Mission, like other Native boarding schools, were poorly kept and have ended up scattered and in the hands of both public and private institutions. Information has been gathered from university and museum archives, government records, books, and public documents such as census, birth, and death records.

What We Learned

Student Records

Because there is no single source of records for the mission, there are also no complete record of students who attended. The names of enrolled students have been pieced together from scattered documents, including grade books recovered after the school building burned in 1985.

The records remain incomplete, with almost no documentation from the 1930s, a decade that accounts for nearly a third of the school’s years of operation. Despite these gaps, Skagway Traditional Council staff have identified the names close to 500 children who attended the mission. The youngest was just three years old.

Inconsistencies have also been found in the records. One example is from the 1940 U.S. Census, which recorded only 21 students at the Pius X Mission, while records from the same year note 75 students, and a class photo shows around 70. We considered the possibility that the 21 listed in the census were official wards of the Mission, while the remaining students may have been counted with their home communities. However, of the remaining students we have names for that year, no census record exists at all for most of them.

Examples like these illustrate how much has been lost through inconsistent recordkeeping. We will likely never recover a full and accurate list of all students who attended the Pius X Mission.

Even for 1940, which has more student names than most years because of the census, we have names for only 31 of the 75 students. For most other years, we have even fewer, and for some, we have no names at all.

Where They Were From

In the fall of 2024, staff reviewed multiple sources in an attempt to identify the home communities of these students. So far, they have been able to determine the hometowns or villages for only a small portion of them.

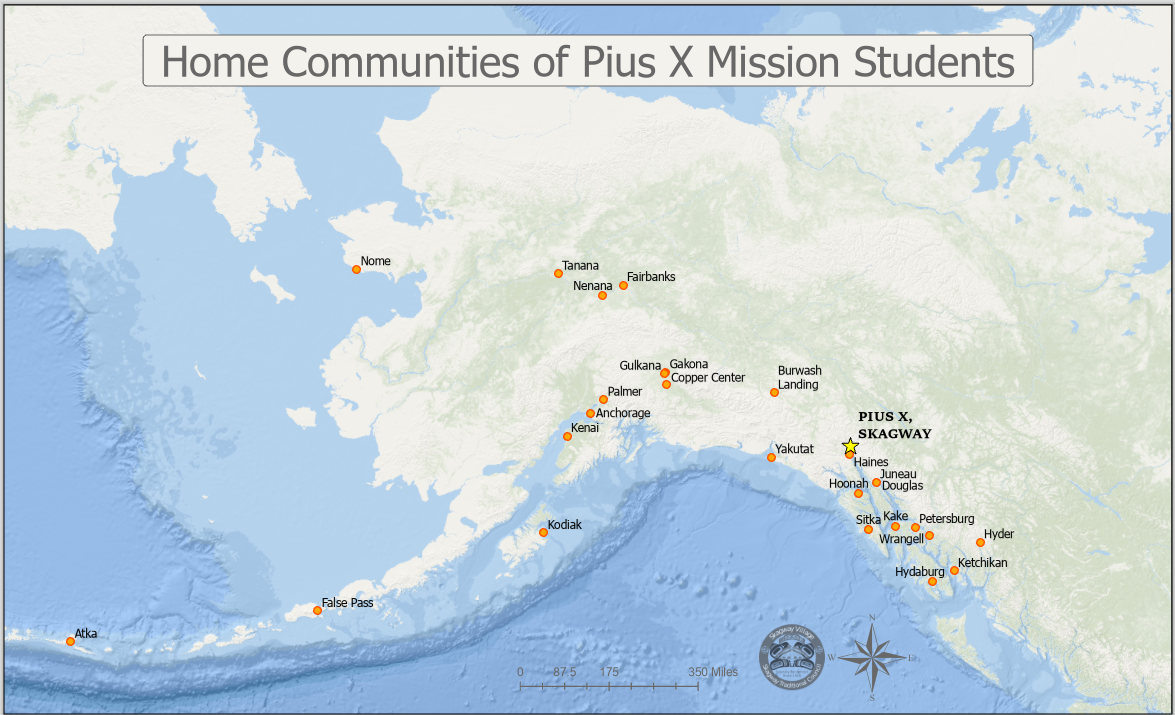

To help illustrate how many communities were affected, and how far many children were taken from their homes, staff created a map showing the known origins of students brought to the Pius X Mission School.

In 2019 and 2020, the Dioceses of Juneau and Anchorage published letters outlining the results of investigations into sexual misconduct involving minors or vulnerable adults by individuals who served within their dioceses. Both lists included priests who had served at or stayed at the Pius X Mission.

To better understand the potential risks of sexual abuse faced by the students at the mission, Skagway Traditional Council staff conducted a thorough review of records, identifying the names of all priests who had served or stayed overnight at the mission. A total of 124 priests were identified. These names were then cross-checked with known abusive priest databases. Of the 124 priests associated with the Pius X Mission, four have been confirmed of or accused of abuse. It is important to remember that abuse, especially against children without support systems, often goes unreported.

Recollections of time at the school also suggest that a non-priest male staff member acted inappropriately with students, though no specific accounts of sexual abuse have been documented.

The Priests and Abuse

(Click to read)

(Click to read)

Father Gallant Land Records

While researching the history of the land where the Pius X Mission was located, Skagway Traditional Council staff discovered that Father Gallant, the founder and principal of the Pius X Mission, owned a significant amount of land in Skagway during his time living there. Staff identified 57 lots in town and 64 acres across the river owned by Gallant. Of the town lots, 24 were used for the mission, and at least two others contained the land where Gallant’s home was located. The 64 acres across the bridge were, at least in part, used for the mission’s dairy. The intent of the remaining land is unclear. Between the time Gallant left Skagway and his death, he sold or gifted all of his land, with a considerable portion going to Father Cowgill and the church.

Sisters of St. Ann Chronicles

In 2023, the Sisters of St. Ann granted the Skagway Traditional Council access to their archival records related to the Pius X Mission, while custody of their archive was being transferred to the Royal BC Museum. These materials included correspondence, photographs, and, a detailed set of internal chronicles kept by the Sisters during the school’s operation. These records offer a valuable window into the daily life of the Mission, most significantly during the 1930s and 1940s, a period when student records are otherwise extremely limited or missing.

The chronicles document the comings and goings of students and staff, illnesses, celebrations, supply shortages, and the seasonal routines that shaped life at the Mission. While the records reflect the worldview of the Sisters, as Euro-American Catholic missionaries, they remain one of the most detailed sources available for understanding how the Pius X Mission operated on a day-to-day basis. They provide critical context for interpreting the school’s history, especially when compared alongside photographs, government documents, and the accounts from former students.

The records recovered from the Royal BC Museum are currently held under an agreement with the RBCM Archives with access restrictions, which means we are able to share what we have learned from them, but cannot disclose certain details or any personally identifiable information. We are engaged with the RBCM archives in hopes of someday gaining agency over these records, so that the Skagway Traditional Council can make its own decisions about what information may support healing and understanding, and what is better kept private out of respect for former students and their families.