Reflection

This page is a space for those who want to better understand and connect with the history and impact of the Pius X Mission and the broader system of Native boarding schools.

The information and questions here are meant to help you consider not only what happened in the past, but also how those events continue to affect people, families, and communities today.

You can reflect on the questions, discuss them with others, and revisit them as you learn more.

By reflecting, you become part of the ongoing work to remember, understand, and help create a future where such harm is not repeated.

Boarding School Purpose

Native boarding schools, like the Pius X Mission in Skagway, were part of a national system designed to assimilate children by removing them from their homes and communities. These schools were often presented as offering education, opportunity, or even a safe haven; however, their underlying purpose was to erase Native cultures and force children to adopt new languages, religions, and ways of life.

While the stated mission sounded positive to some outsiders, the reality was that these schools worked to replace Indigenous identity with Western values and traditions. Understanding both how they were portrayed and what they truly did helps us see these schools as deliberate tools of cultural assimilation rather than neutral or helpful institutions.

Reflection Questions:

Why might the government and church have wanted to assimilate Native children? What do you think “successful” assimilation looks like to them?

Alaska Native children were often sent to school far from their homes, sometimes hundreds of miles away rather than to the nearest school. Why do you think that was?

Why might some Native children and families have felt they had no choice but to send children to these schools?

Do you think the people running boarding schools believed they were helping Native children?

What ideas or influences do you think lead the Euro-American settlers to feel justified in their mission to educate and assimilate Native children into western culture and religion?

What do you think people were told about the purpose of boarding schools when they were operating? Did people view them as tools of assimilation? Would people at the time have thought assimilation was a good or a bad thing?

How might the public perception of these schools have been different if the truth about the conditions and impacts was widely known?

What is Assimilation?

Assimilation means being absorbed into another culture, often at the cost of giving up your own. In the context of Native boarding schools, assimilation was not a choice. Children were pressured or forced to abandon their languages, traditions, beliefs, and even their names, while being made to adopt the language, religion, and customs of the dominant culture.

It’s important to remember that cultural assimilation like this is not about blending cultures but rather about replacing one culture with another.

Why Alaska Native Families Faced Hard Times

Boarding schools were sometimes perceived as “safe havens,” often framed as rescuing children from poverty or difficult home situations. What is rarely acknowledged is that these hardships were not accidental. They were caused or worsened by decades of government policies and outside interference.

Some of the factors that created these conditions included:

Loss of traditional lands and resources – Colonization and government land seizures disrupted hunting, fishing, and gathering practices that sustained communities for generations.

Economic displacement – The shift to a new cash-based economy, paired with exclusion from many jobs, left families struggling to adapt while facing high unemployment.

Suppression of culture – Bans on traditional languages, ceremonies, and ways of life weakened social structures and community cohesion.

Health crises – Epidemics, introduced by outsiders, devastated populations and left lasting impacts on family stability and well-being.

Intergenerational trauma – Previous generations who endured boarding schools or forced relocation carried emotional wounds that affected family life.

Understanding these root causes shifts the focus from blaming families for “hard times” to recognizing the systemic harm that made those times so hard.

Loss of Tradition, Culture and Language

One of the devastating impacts of the boarding school era was the deliberate erasure of Indigenous languages, cultural practices, and traditional knowledge. Children were often punished for speaking their Native language or practicing their customs. Often, even small acts of cultural expression were forbidden. At the same time, schools like Pius X Mission required participation in Western and Christian values and traditions.

Over time, this forced separation from language and tradition disrupted the way culture was passed from one generation to the next. Many students found themselves no longer fluent in their own language and struggling to reconnect with community life when they returned home. Despite these attempts to erase identity, many families and Tribes have worked to preserve and revitalize their languages, stories, and ways of life.

Reflection questions:

Why do you think those running boarding schools felt it was important to keep Native students from speaking their language rather than teaching them English while also letting them speak their native language?

Shaming or punishing students for speaking their language was common in Native boarding schools. How do you think shaming children as a deterrent for speaking their language might have impacted their connections with family and culture even when away from the school?

Think about traditions, family recipes, special holidays, or stories in your family growing up. Did you or will you carry any of those on? Do you think that is important? Why?

How does language play a role in shaping a person’s identity and view of the world?

Using traditional place names is a way of revitalizing culture and language. What are some other ways to support revitalization?

Why does language matter?

Language is more than the words we use. It carries the worldview, humor, ceremonies, beliefs and the values of a people. When a language is lost, so are unique ways of seeing the world.

For many Indigenous peoples, the effort to restore language is also a way of restoring knowledge and healing from the boarding school era.

Today, there are individuals, and organizations dedicated to preserving indigenous languages. Here, University of Alaska Southeast offers language classes in Haida, Lingít, and Tsimshian. You can also find online resources and local classes and groups to join. Even so, Lingít, like many indigenous languages is endangered.

Impacts on Students, Families and Communities

The boarding school system hurt more than the children who attended the schools. It deeply impacted entire families and communities. Parents were often forced or pressured to send their children away to schools hundreds of miles away. Some never returned. Families were left to grieve the loss of their children, and the adults in the families and communities lost the sense of purpose that came with caregiving, passing down knowledge, and teaching skills to the next generation.

Students who returned often struggled to reconnect with their families and communities. Some no longer spoke their Native language, while others carried trauma from years of punishment, neglect, or abuse.

The coping mechanisms students developed from their time in boarding schools often followed them into adulthood and some students raised in missions, had little idea what a family life looked like. These wounds and coping strategies can impact future generations in many different ways as the survivors and their families navigate the aftermath of harm done in the boarding schools.

Reflection Questions

How would a community be effected if most of its children were taken away?

The last federal Indian boarding school closed in 1980 in the U.S.. How old were you, your parents, or your grandparents in 1980? Why is it important to remember how recently Native boarding schools were still operating?

How could the loss of language in one generation affect the generation before and the next generation? Do you speak the same language as your grandparents?

What is intergenerational trauma?

Intergenerational trauma happens when the effects of a traumatic experience are passed down from those who lived through it to their children and grandchildren. It is carried through the ways people learn to cope, communicate, and relate to others after harm has occurred.

For survivors of Native boarding schools, this might look like a child sensing her mother’s fear when someone knocks on the door, because, for her mother, a knock like that used to mean being taken away. It might also appear as a parent who struggles to show love or guide their child through emotions because they never experienced that kind of care themselves.

In the boarding school system, trauma came from being separated from family, punished for speaking one’s language, shamed for identity and culture, and growing up without the warmth and safety of home. Many students also endured sexual abuse, harsh physical punishment, or psychological harm, leaving them with lasting fear and shame.

Recognizing intergenerational trauma helps us understand why healing takes time and should include entire families and communities.

Healing and Reconciliation

Healing and reconciliation are part of an ongoing process that continues today. Across Alaska and throughout the U.S. and Canada, indigenous communities hold gatherings, language classes, and memorials to honor survivors and remember those who never came home. Churches and government institutions have begun offering formal apologies, returning land, and sharing records.

For many, healing and reconciliation means restoring connections to language, land, family, and identity while facing the truth and working to rebuild trust through action and respect. These efforts remind us that healing takes time, honesty, and care.

Reflection Questions:

What might healing look like for individuals? families? and communities?

The terms “healing” and “reconciliation” are often paired when talking about the Native boarding school legacy. What do each of these look like, and how are they different from each other?

Most adults in the U.S. never learned about native boarding schools when they were in school. Why do you think schools didn’t teach kids about boarding schools?

Why is education about Native boarding schools and remembrance important?

For many, their time at boarding schools represents trauma in their past. When is it appropriate to ask a boarding school survivor about their experiences? What are some strategies for being careful and respectful when learning from boarding school survivors?

What could the Skagway community do to help former students and their families heal?

Do you think it is important for the Skagway community to acknowledge and remember the Pius X Mission? Why is acknowledgement important?

Many of Skagway’s community members talk to thousands of people every summer. Do you think Skagway could play a role in educating people about Native boarding schools? What are some pitfalls tour guides could fall into when sharing sensitive cultural history?

What is a Right to Silence?

Right to Silence means that survivors of trauma have the right to choose when, how, and if they tell their stories. Recounting trauma can be painful, exhausting, or even unsafe. Healing looks different for everyone, and giving people control over their own stories is an essential part of that process.

Sharing experiences and educating others is an important part of learning as a society and preventing future harm, but it must always be balanced with respect for survivors’ health, safety, and autonomy. Be thoughtful when asking about boarding school experiences. Make sure the person is comfortable sharing, ask questions in safe spaces among trusted people, and never bring up painful topics without care or warning.

Orange Shirt Day in Skagway, 2025

Reconciliation takes time and change.

Over the past three decades, churches, religious organizations, and governments have issued statements of apology and remorse for their direct or indirect roles in the Native boarding school system. Some have taken meaningful steps toward reconciliation through returning land where schools or missions once operated, offering monetary reparations, or cooperating with records retrieval and transfer. These gestures are powerful; however, the organizations that participated in the harm are not always interested in, or ready, to participate in the healing and reconciliation process. It is a harsh truth that the mindsets and ideas that led to the cultural erasure of the boarding school era still persist today.

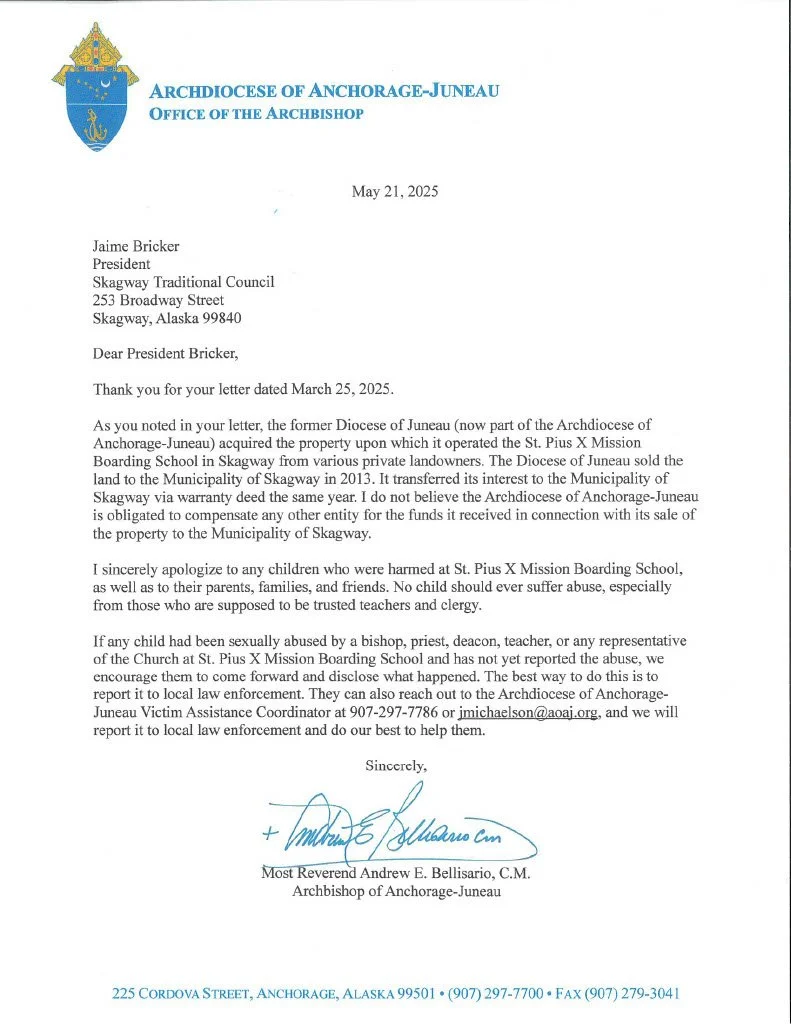

Early in 2025, the Skagway Traditional Council sent a letter to the Catholic Diocese of Anchorage-Juneau asking them for two actions regarding the Pius X Mission Boarding School in Skagway.

First, STC asked the Diocese to formally acknowledge and apologize for the harms that were done through its role in operating the school, which was part of the federal Indian boarding school system that forcibly assimilated Alaska Native children and where students suffered physical, sexual, and emotional abuse.

Second, STC requested that the Diocese provide compensation to the Tribe for the value of the land where the school once stood. The letter noted that when the school closed, the land was sold by the Diocese to the Municipality of Skagway rather than being offered back to the Tribe, despite the Tribe’s expressed interest and desire to reclaim it.

The letter pointed to apologies and actions from other religious organizations in recent decades, as well as those from President Biden and Pope Francis, as examples the Diocese could look to for how to engage in the healing process.

In its reply, the Diocese limited its apology to a mention within their written response and to cases of abuse at Pius X Mission School, as well as provided instructions for survivors to report abuse. The letter does not address the systemic or lasting harm of the Native boarding schools, nor the cultural and historical trauma inflicted on the Alaska Native community. The response also declines to address STC’s request for reparative action regarding the former mission school property.